Beshalach (Exodus 13:7-17:16): January 30, 2021/17 Shevat 5781

When the Continental Congress declared the independence of the United States in 1776, one of the first things they did was commission a committee to design a seal for the new nation. While the design that was ultimately adopted was the familiar Great Seal of the United States, one of the original proposals, suggested by Benjamin Franklin, showed the Israelites having just crossed the Red Sea, with Moses commanding the waters to return to their places, drowning Pharaoh and his army. This scene, arguably the most famous of all miracles chronicled in the Torah, is the climax of Parashat Beshalach, a parashah replete with miracles.

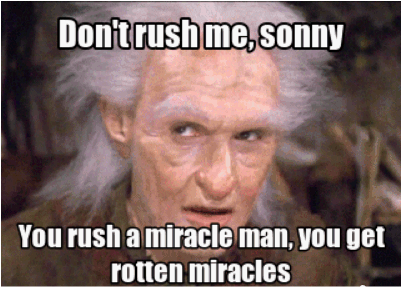

What is a miracle? In the Rugrats Hanukkah special, the babies define it as "when something good happens that you thought could never happen." We tend to associate miracles with totally supernatural occurrences - rivers turning to blood, seas splitting, manna and quails falling from heaven - and if we can find rational explanations for those phenomena, then we have disproven their miraculous nature. But that isn't a complete understanding of miracles. If we look at the text of this week's parashah, the splitting of the Red Sea (which, it is worth noting, may not be the same body of water as the one presently known by that name) was not quite the sudden, magical partition that we tend to picture. The Torah describes the scene thus: "Moses extended his arm over the sea, and God pushed back the sea with a mighty east wind all night, turning the sea to dry ground, and the waters were split." A powerful and prolonged wind is certainly something within the range of natural possibility, but that doesn't make it any less of a miracle. What's miraculous is that the wind happened at the right time. Similarly, when we look at the descriptions of divine providence in the book of Jonah, we see that God "arranges" first the giant fish and later the gourd plant. That the fish and the plant existed was not so remarkable, it was the fact that they were in the right place at the right time. We see another incidence of this sort of miracle in the haftarah for this week, at the Battle of Mount Tavor. The Canaanite chariot corps is riding hard to attack the Israelite army when a sudden rainstorm comes, flooding the Kishon River and miring the Canaanite chariots in the now-soft ground, enabling the Israelite forces to charge down the mountain and slaughter their enemies. Anyone familiar with desert weather patterns knows that flash floods are a regular occurrence when heavy rains come, and many riverbeds go from dry hiking paths to raging torrents capable of washing away people in an instant (see the case of the 10 Israeli teenagers killed in a flash flood while hiking in southern Israel in 2018). That such a rainstorm would happen is not noteworthy. That such a rainstorm would happen just as the Canaanite chariots were making their attack is the miraculous part.When I first started my post-secondary education, I was an archaeology major, and I spent two summers working on digs in Israel. One of the things that I found in talking to people outside the archaeology world was that everyone seemed to understand what we were doing as either trying to prove the Bible or disprove it. As one member of a church group which came to work at one of the sites put it (paraphrased, as this was over a decade ago), "We know that Megiddo (the site at which I was working), which is in the Bible, existed, so that means that everything in the Bible must be true." Now, aside from the fact that this is a logical fallacy, it's not the way to understand the more wondrous segments of the Torah. Every minute detail need not be true in a literal sense for other parts to have a historical meaning or significance in developing our identity. Our identity as Jews should be strong enough to sustain itself even if the Nile turning to blood was really some sort of algae bloom and not genuine transubstantiation. The idea that science must take a strong atheist (that is, a positive belief in God's non-existence) stance or the converse belief that religion must necessarily oppose scientific explanations for things that happen in the world is an affront to both science and religion. We may not be able to directly observe God's being - God has no form, and we have no way of comprehending God - but we can observe how God interacts with the universe. That is, in fact, the essence of science. Understanding how miracles happen is not diminishing or denying that they happen. On the contrary, it is a demonstration of God's ability to make miracles in the world any less than understanding that a car (at least one with a gas engine) is propelled by the exploding fuel operating a series of pistons to turn an axle takes away from the fact that a car goes forward when the driver presses the gas pedal.

U R OUR MIRACLE 😇💙 G&G

ReplyDelete